Is Francis a Saint or Sinner? Leo XIV Can’t Decide

Listening, Laudato Si’, and the Lingering Ghost of Francis

On May 25, Pope Leo XIV stood before the tomb of Francis and publicly prayed for his soul. The gesture was solemn. Respectful. Perhaps even moving.

But it was also deeply confusing.

Since assuming the papacy, Leo XIV has referred to Francis as if he were already enjoying the beatific vision; invoking him in heaven, praising his legacy, and aligning his own mission with Francis’s reforms. Now, suddenly, he’s praying for his soul, which can only make sense if Francis isn’t in heaven, or at least if his salvation remains uncertain.

This isn’t a minor slip. In Catholic theology, one does not pray for the dead unless there is real doubt about their final judgment. If Francis is in heaven, prayers are misplaced. If he’s not, then the earlier rhetoric, implying his sanctity and canonizing his legacy, was gravely premature.

But this moment at the tomb was only the tip of the iceberg.

In three major speeches delivered over two days, Leo XIV mapped out the guiding vision of his pontificate. And what emerged was not clarity, correction, or Catholicism-with-backbone, but the same foggy sentimentality that defined his predecessor.

1. The May 24 Address to Vatican Employees: A Bureaucracy With a Soul

In his first speech, Leo XIV addressed employees of the Roman Curia and Vatican City State. He called it a moment not for keynote speeches but “thank yous.” That, at least, was accurate, because the speech offered no theological substance.

Instead, Leo waxed nostalgic about the Curia’s institutional memory. “Popes pass, the Curia remains,” he said. Memory, not magisterium, was the theme. The Church becomes a continuity machine; something that preserves the papacy rather than being defined by it.

Then came the invocation of Francis.

Leo praised Evangelii Gaudium and Praedicate Evangelium: documents that dismantled traditional Roman structures and enshrined evangelization as dialogue rather than conversion. He called the Church to be “missionary,” but then defined that mission as welcoming, bridge-building, and “readiness to dialogue.”

No mention of heresy. No defense of truth. No reference to the conversion of sinners or the kingship of Christ.

And when Leo described the Church’s unity, it was rooted not in doctrine or sacraments, but in collegial behavior, patience, and “a good dose of humor.” A reader might fairly ask: Is this a Church or a human resources seminar?

2. The May 25 Regina Caeli: Everyone’s a Tabernacle Now

The next day, Leo offered his Regina Caeli reflection to the faithful in St. Peter’s Square. He chose the Gospel of John: “We will come to them and make our home with them.” But instead of anchoring that indwelling in baptism or grace, Leo XIV launched into a sentimental meditation on divine accompaniment.

“Despite my weakness,” he said, “the Lord is not ashamed of my humanity.”

It’s a warm thought, but dangerously misleading when untethered from Catholic theology. In traditional doctrine, God does not dwell in every person by default. His indwelling depends on sanctifying grace, which is lost through mortal sin and restored through confession and penance.

Yet Leo speaks as if the entire world is already a dwelling place of God. He calls each of us a “temple,” says that love “spreads outwards to others,” and concludes that “each of our sisters and brothers is a dwelling place of God.”

This is not Catholic doctrine. It is postconciliar mysticism. Moral universalism cloaked in biblical language.

Then, in a passage that should make any Catholic raise an eyebrow, Leo praised Laudato Si’ on its tenth anniversary. He reaffirmed the “twofold cry of the Earth and of the poor.” He hailed the global movement it inspired. There was no mention of abortion, sacrilege, or doctrinal crisis; just the weather.

Traditional Catholics might ask: When did carbon emissions replace original sin?

3. The May 25 Lateran Homily: Listening Is the New Magisterium

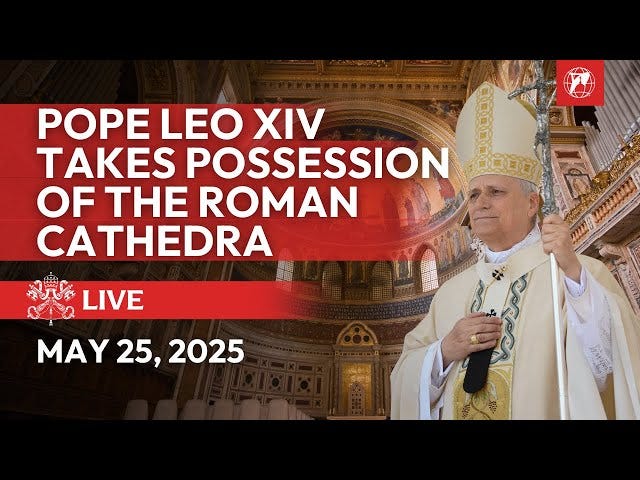

Later that same day, Leo XIV delivered his homily at the Basilica of St. John Lateran for his official possession of the Chair of the Bishop of Rome.

It was, theologically speaking, the crown jewel of the weekend’s ambiguity.

He described the Church of Rome as “Mater omnium Ecclesiarum”—Mother of all Churches—but then reframed her maternal character as “tenderness, self-sacrifice, and the capacity to listen.” These traits are admirable, but they are not what defines the Church’s mission. The Church is also teaching, judging, governing, and sanctifying. None of that made it into Leo’s vision.

He repeatedly returned to the idea of listening; to the world, to one another, and within the Church. He cited the Council of Jerusalem not to affirm apostolic authority, but to show the value of dialogue and shared discernment. He praised the Diocese of Rome for its synodal conversations. And in a revealing phrase, he said he hopes to “decide things together.”

That’s not how the papacy works.

Then came a string of theological evasions: God’s word is written “on our hearts” (no mention of the Church’s magisterium); we are “letters of Christ” (no reference to confession or Eucharist); we must embrace “bold projects” and “prophetic initiatives” (but no guidance on what is true or false).

Even the saints were weaponized. St. Augustine was quoted as a listener. St. Leo the Great as a humble vessel. No fire. No clarity. No battle cry. Just gentle noises from history’s loudest lions.

4. The Problem of Francis: Canonized in One Breath, Commemorated in the Next

And then came the moment at the tomb.

Just hours after re-affirming Francis’s legacy, Leo XIV went to Santa Maria Maggiore and publicly prayed for his soul. Vatican media captured it. CatholicSat posted it. Everyone saw it.

But few noticed the contradiction.

This is the same Leo who had, just days earlier, spoken of Francis as if already in heaven. In prior speeches, he spoke of Francis’s wisdom, sanctity, and inspiration as if they were obvious and final. Now, suddenly, he’s offering suffrages for his soul; something the Church has never done for a canonized saint.

So which is it? Is Francis a canonizable shepherd of the new Church, or a soul in need of mercy?

The answer is simple: This contradiction is the inevitable result of a Church that canonizes confusion and sentimentalizes everything else.

Conclusion: The Church of Sentiment Cannot Save

Leo XIV may bow more deeply than Francis, but he bows to the same ideology. His speeches show no break with the errors of the past decade; only their continuation in softer tones and finer vestments. Francis dismantled the Church’s doctrinal identity. Leo seems content to light a candle at the wreckage and write poetry about it.

This is not reform, but repetition with better manners.

And if the early days of Leo’s pontificate are any indication, we are not entering a new springtime. We are still lost in the same fog. The only difference now is that it smells faintly of incense.

Fog smelling like incense. Fabulous!

How do you know what he was praying for? Since he already canonized him—and Francis the False is after all truly patron saint of the Lavender Mafia (including the episcopal Charlotte & St. Gallen Clowns)—he may have been imploring his aid.